JBIC History vol.4

In 1985 the Plaza Accord was signed to adjust exchange rates, and Japan faced a sharp appreciation of the yen. At that time, JBIC’s predecessor, the Export-Import Bank of Japan (JEXIM), played an integral part in resolving international trade friction.

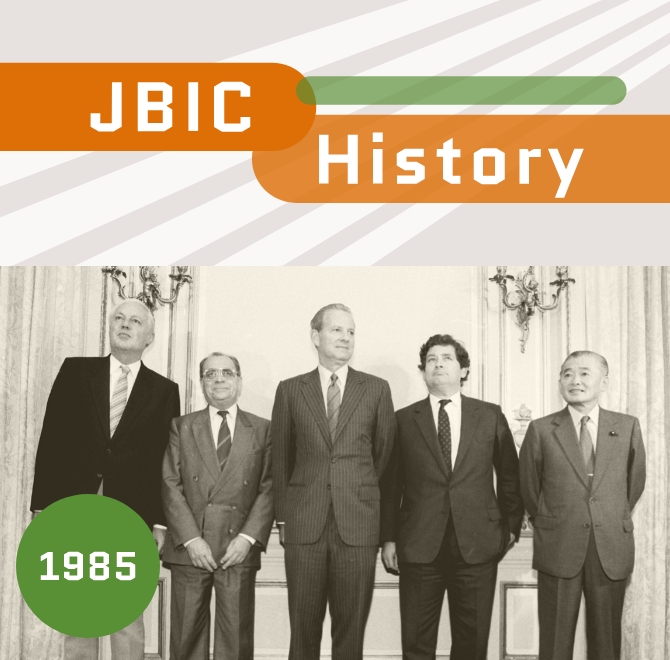

Finance ministers of the G5 nations—France, Germany, Japan, the U.K., and the U.S. met at the Plaza Hotel in New York on September 22, 1985. The agreement that was signed to reduce the strength of the U.S. dollar is known as the Plaza Accord. Photo: The New York Times/AFLO

As Japan's trade surplus grew, friction escalated into a trade war

After the second oil crisis of 1979, which caused rising prices and a deterioration of the balance of payments, early measures taken to control inflation returned Japan's current account balance to surplus in 1981. The international competitiveness of Japanese products, which incorporated energy-saving and semiconductor technologies, rose rapidly, increasing the trade surplus with the U.S. by 2.5 times, from USD 13.3 billion in 1981 to USD 33.2 billion in 1984.

In turn, Western countries became very critical of Japan, targeting the promotion of imports and opening of markets, and even structural changes for the Japanese economy and way of doing business. This friction intensified to the point that in 1985 it came to be called the Japan-U.S. trade war.

Japan’s government worked to resolve this with measures including active use of JEXIM’s functions in the implementation of emergency foreign currency loans for imports, promotion of industry cooperation, and development of import loan systems. In 1984, the Export-Import Bank of Japan Act (JEXIM Act) was amended as a measure to promote imports, facilitating import financing such as low-interest loans for product imports, as well as making foreign corporations eligible for import loans.

While Japan’s trade surplus expanded, the U.S. in the early 80s confronted twin fiscal and trade deficits, becoming a net debtor nation in 1985. The Reagan administration, through its "Reaganomics" economic policy, adopted a "small government" approach. And with its top priority after the oil crisis being to overcome inflation, introduced high interest rates, which in turn caused the dollar to appreciate.

In order to correct this excessive appreciation of the dollar through currency adjustments, the Plaza Accord was signed by the G5 nations in September 1985. The yen appreciated against the dollar by an annual rate of around 20% in the three years after the accord, going from 240 yen to the dollar just before the agreement, to 127 yen three years later.

Foreign direct investment surges, stock and land prices soar

Japan then faced a recession caused by this appreciation of the yen. In response to the strong yen, foreign direct investment (FDI) grew at an unprecedented rate—increasing annually by USD 10 to 20 billion from 1985 to reach a record USD 67.5 billion in 1989.

The Japanese government also placed importance on promoting FDI as a way to shape an internationally balanced trade and industrial structure, and to contribute to the global economy as a creditor nation. The JEXIM Act was also amended in 1985 and 1989 to enhance support measures for FDI.

In addition, the government took measures to expand domestic demand. The Bank of Japan also lowered the official interest rate (base rate) in stages, and the economy recovered robustly. However, against the backdrop of excessive liquidity arising from the current account surplus, expectations of continuous price rises led to an extraordinary surge in stocks and other assets. The Nikkei Stock Average, which had hovered around the 10,000 mark in 1985, rose sharply and hit an all-time high of 38,915 at the end of 1989.

But the asset bubble, which had become detached from the real economy, burst after peaking in 1990. Banks and businesses were left holding huge amounts of bad debt and liabilities. This was the start of Japan’s economic stagnation.

■Japan-U.S. economic friction

and JEXIM’s expanded functions

| 1981 | April | Voluntary export restraint on automobiles exported to the U.S. |

|---|---|---|

| 1983 | November | U.S. President Reagan visits Japan. |

| Requests market opening and deregulation. | ||

| 1984 | May | JEXIM Act amended (expansion of import loans) |

| 1985 | June | JEXIM Act amended (development of overseas investment loans, etc.) |

| September | Plaza Accord | |

| 1989 | June | JEXIM Act amended (creation of investment function, etc.) |

| December | Nikkei Stock Average reaches all-time high |