Shifting geopolitical landscapes, the reality of the Global South, the risks of climate inaction, and Japan’s role in the world—Parag Khanna, global strategy advisor, author, and CEO of AI-driven geospatial analytics platform AlphaGeo, offers his thought-provoking insights and unique perspectives in a deep dive into these topics and more.

Founder & CEO of AlphaGeo, an AI based geospatial predictive analytics platform

PARAG KHANNA

Born in India and raised in the United Arab Emirates, New York, and Germany, Parag Khanna has a Ph.D. from the London School of Economics, and Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Georgetown University. Founder and CEO of AI-powered geospatial analytics platform AlphaGeo, he is a bestselling author of seven books and has appeared in the media and advised governments around the globe.

If we hold the West to be the standard of such behavior, and NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) in particular, then we would not see a great deal of unity, harmony, comity, or coordination. It’s generally speaking the U.S., and then whoever wants to join on a case-by-case basis.

In other words, the global backdrop is that alliances have been replaced by what I call multi-alignment. And multi-alignment is the term that I developed about 20 years ago to describe this world of very opportunistic and self-serving behavior, in which every country sees itself as the center rather than necessarily hewing to rigid alliance formations. Another way to put it is that it is a world of dalliances, not alliances.

So, we see novel formations. It’s not to say that we don’t have cooperation and that we don’t have mutual interest. Of course we do.

You can see that, for example, with the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, consisting of Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.), which of course Japan is a founding member of. You can see it with BRICS (originally an investment concept covering Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa; now a geopolitical grouping that has added Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia).

We call these clubs rather than alliances in international relations theory and international political economy. If we apply that same logic to the Global South, of course those countries are not going to act in a coordinated way, because the broader context is one in which countries don’t do that anymore.

That’s particularly true for the Global South. First, they don’t have anything in common other than being post-colonial countries. They are many different regions of the world: Latin America, Africa, West Asia, the Arab world, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Most of the world is post-colonial, and most of the world is the South. Within the Global South, I tend to look regionally and say, is South America becoming more cohesive, better coordinated, better integrated? Is Africa? Are the Gulf countries?

So, when it comes then to transnational or international multilateral cooperation among countries of the South, you are left with things like BRICS or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO, a regional grouping led by China and Russia for economic and security issues) and things like the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a lender for regional infrastructure projects led by China focused on developing economies).

But note that China is the principal hub of all of those bodies, and is it really part of the Global South? China is a structural superpower in the global system.

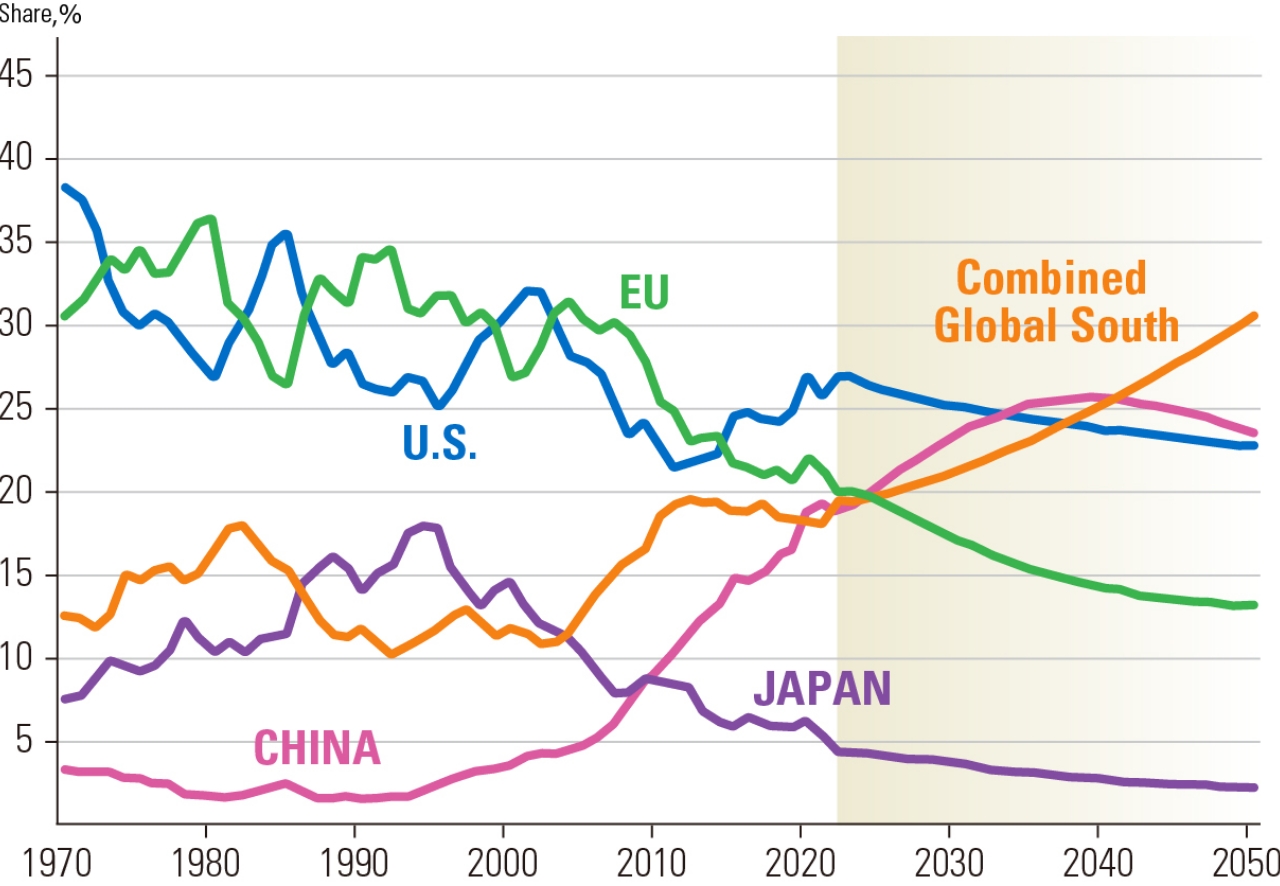

The GDP of the Global South is projected to surpass that of the U.S. and China around 2040.

*The Global South refers to the G77 member states, excluding China. Graph data sourced from Mitsubishi Research Institute (historical data from IMF, projections by Mitsubishi Research Institute), partially modified for use.

(Note: Projections as of July 2023, aggregated from countries with available data.)

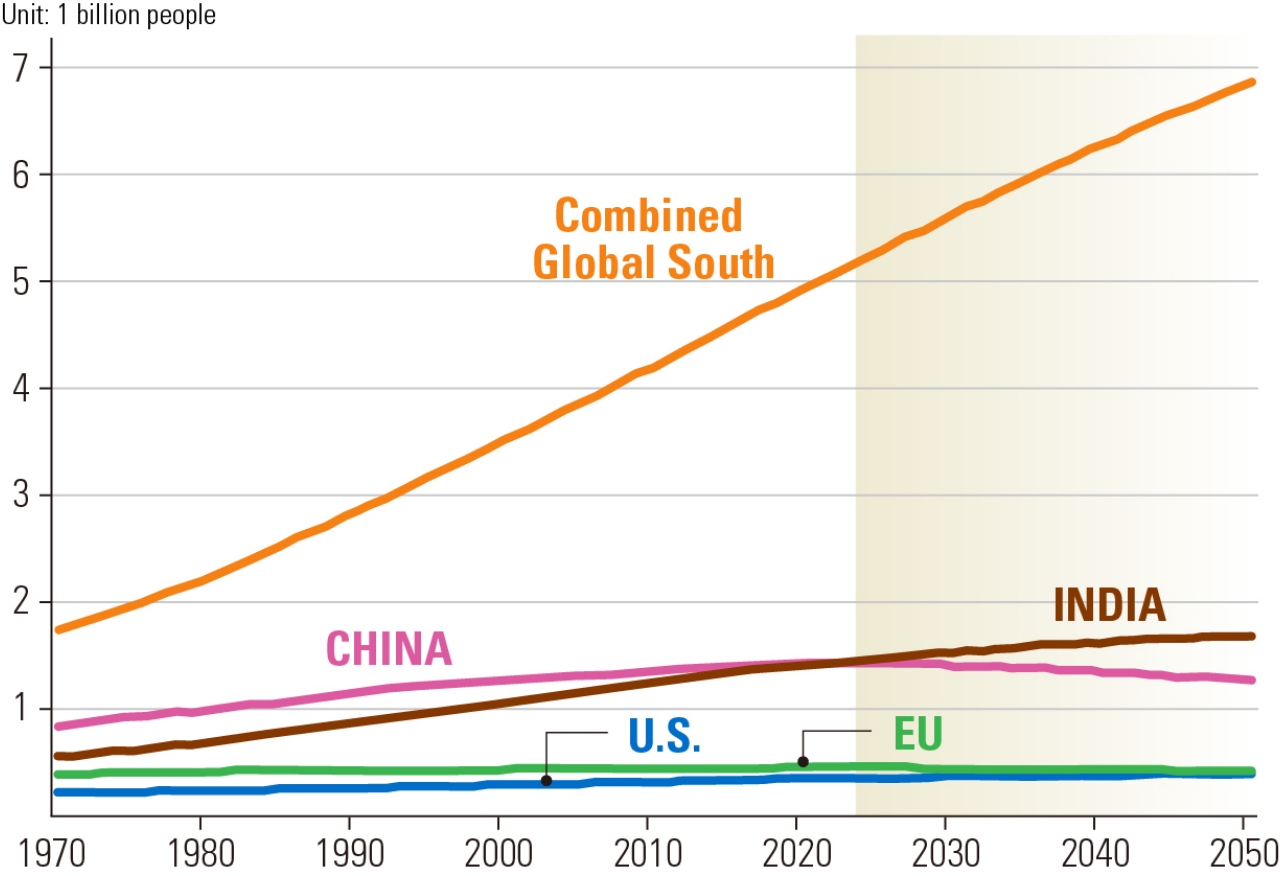

The Global South, including India, is expected to continue experiencing rapid population growth and is projected to account for 70 percent of the world's population by 2050.

*Graph data sourced from Mitsubishi Research Institute (based on the United Nations' "World Population Prospects 2024" created by Mitsubishi Research Institute), partially modified for use.

But it’s much like the term Islamic World. If we were having this conversation 20 or 22 years ago, we’d be talking about the Islamic World because after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, everything was about the West and the Islamic World. That term faded away. It never really meant anything; two Muslim countries don’t coordinate behavior on anything.

I don’t expect the Global South to amount to much more from a diplomatic standpoint. If it’s going to be the new way in which we talk about the Third World or developing countries, that’s just nomenclature. But I’m very interested in the Global South from the standpoint of seeing which specific states, which specific sub-regions are exhibiting their own confidence, taking things in their own direction, making their own policies and strategies, acquiring more leverage and diplomacy, and negotiations. Those are very important and fascinating issues.

In the post-colonial world, these are countries that by definition have only existed for the past 75 years. The last thing they want is to be subsumed into some architecture that suppresses their freedom and autonomy and sovereignty. They’re coming out of centuries of colonialism, so they don’t want to be a pawn of China’s or to join a new Western alliance, or to be lumped together with others.

They absolutely jealously guard their own independence and freedom. If you look at it from the top down, then all you see is: Are you with the U.S.? Are you with China? Are you East or West? I view the world in the exact opposite way. The answer to the question depends on the behavior of 150 other countries. But to know if China and the U.S. are going to get what they want, you have to look at how everyone else behaves, and they don’t behave as one. That’s what makes the world so interesting.

And clearly, they are doing something, and therefore, they matter. I’m very interested in the role of BRICS, AIIB, SCO, Belt and Road Initiative (an international infrastructure development project launched by China in 2013), RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free trade agreement signed in 2020 covering ASEAN, Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea)—all in Asia primarily—but then also of course Quad and AUKUS (a security agreement between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific region).

I’m a big fan of all of these. This is the emergence of new vectors, new corridors of diplomacy and cooperation, again from the bottom up. This is sideways. This is not being forced by the U.S., or by China, or by Europe. This is the flourishing of connectivity, diplomatically, commercially, infrastructurally, financially, and technologically across hundreds of countries.

I live in Singapore; every country in the world comes here to learn how to run their country. This is the most successful post-colonial country in the world. I am affiliated with the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, part of the National University of Singapore, and we receive delegations of ministers, mayors, ambassadors, and governors every week from every country in the world. One of the smallest countries in the world teaches every other country in the world how to run a country.

There isn’t one model anymore. Just in terms of lessons, in one of my books, I call this “the next best thing.” The theory of “the next best thing” is that each country, generally speaking, can only aspire to achieve something that is attainable.

So, the model for Afghanistan is not Switzerland. Not by a mile. The model for Mongolia is not Switzerland, it is Kazakhstan. They’re landlocked countries, mildly democratic, coming out of authoritarian Soviet influence or domination. They’re resource-rich economies, sparsely populated, and have harsh climates. They don’t have the luxury of aspiring to be like Denmark or Japan.

Japan is truly the most stable liberal democracy in the world, but it’s unattainable to be like Japan for every other country in the world right now. You can take a lot of investment from Japan, study Japan, be inspired by Japan—but are you going to be Japan? Of course not. And the beauty of the dialogue of the Global South is that they can see from each other who has done those little incremental things that the others can learn from.

But the answer is different if you are India, Ukraine, Iran, or even Mexico. Countries are going to pursue their interests, and if the U.S. is their friend, they’ll want to remain friends no matter who is president. But they’ll also pursue their own interests no matter who is president.

Sometimes, those get underestimated, and I think that’s unfortunate. For example, a lot of people act as if the new Silk Roads and the new trade routes across Eurasia didn’t exist until China’s Belt and Road Initiative 10 years ago. I point out that Europe and Japan have been investing in infrastructure projects across Eurasia for decades. China is amplifying a movement for Eurasian connectivity that’s already existed.

Again, I think more regionally. Japan in Southeast Asia and Japan in India are more important than Japan in the Caribbean or Japan in Africa. So as someone who lives here in this region in Southeast Asia and as someone who follows India, I’m very aware that Japan is a very strong and steady presence and influence across South and Southeast Asia and these are the most important regions to be focused on anyway.

But investment is less fungible. If you don’t invest somewhere, maybe someone else will not invest there. Therefore, investment is a very important way to build deeper bonds and ties, to drive economic growth, and to have a strong structural relationship with countries. And now is a very dynamic time. There’s a lot of competition for supply chains, for attracting manufacturing and other sectors. I’m a believer that Japan can play a very fundamental role there.

These are all the contributors to Japan’s economic condition. There’s one school of thought that says, this is normal, but at least the Japanese have an amazing quality of life. On the other hand, there are concerns about the future. The population is declining, there isn’t enough broad-based innovation. Other countries are hugely competitive and are eroding Japan’s leadership in many sectors. There is some sense that it’s living on borrowed time. Japan and Germany are really quite similar in that way.

Therefore, unless you constantly nurture and invest in being cutting-edge and innovative, then you will lose that edge. I share that concern. I think the future of Japan will have to be more muscular in terms of having to pick sectors where it really wants to maintain a strong lead and invest a lot and defend that edge. It is clearly committing a larger R&D budget toward AI, semiconductors, and robotics. And it will have to become proactively competitive with export promotion in these areas otherwise they will be dominated by China, if they’re not already dominated by China.

And finding a country’s niche in global value chains and investing to help it: What is their value? What is their best opportunity? Is it food processing, manufacturing, renewable energy, or batteries? That really should be central to JBIC’s investment focus worldwide as an agent of building Japanese influence.

International Political Scientist, Founder & CEO of AlphaGeo

PARAG KHANNA